The Women in Tech Problem Is Not Awareness. It’s Power.

Every year, the technology industry pauses to talk about women. Reports are published. Panels are organised. Companies restate their commitments. Then the moment passes, attention shifts elsewhere, and the numbers barely change.

The problem is not a lack of discussion. It is that the conversation itself has become detached from how power, careers, and risk actually function inside technology companies.

A new global study from Acronis, “FOMO at Work: The Opportunity Gap Between Men and Women in Tech,” exposes this gap with uncomfortable clarity. Based on a survey of more than 650 IT professionals across the United States, Europe, and parts of Asia, the report does not point to a sudden regression or a dramatic new barrier. Instead, it shows something more persistent: men and women are operating inside the same industry but experiencing opportunity, fairness, and career risk very differently.

Women currently represent approximately 29% of the global technology workforce. That figure has moved only marginally over time, and critically, it has not translated into proportional leadership or decision-making power. The Acronis survey reflects this reality directly, mirroring global participation rather than aspirational targets.

The System Isn’t Frozen, But It Isn’t Honest Either

Alona Geckler, SVP Business Operations and Chief of Staff at Acronis, has spent more than two decades inside technology organisations. She is careful not to frame the problem as stagnation alone.

“I understand the frustration very well, because when you look at the change year over year, it feels slow and sometimes discouraging,” she says. “But when you zoom out over a longer period, you do see movement. The issue is not that the system is frozen. It’s that the change is incremental, and we often talk about it as if it’s transformational.”

That gap between narrative and reality runs through the entire report. Progress exists, but it is fragile, uneven, and often overstated. Female representation inches forward, yet influence lags. Women are present, but authority remains concentrated.

“The bigger issue, in my view, is how we talk about women in tech,” Geckler adds. “Too often it becomes symbolic — women in the room without real influence or responsibility. That doesn’t change outcomes. What changes outcomes is when men are part of the conversation, because this is not a women-only issue. It’s a business issue.”

Alona Geckler, SVP Business Operations and Chief of Staff at Acronis

The Perception Gap No One Wants to Own

The Acronis data makes that business problem visible.

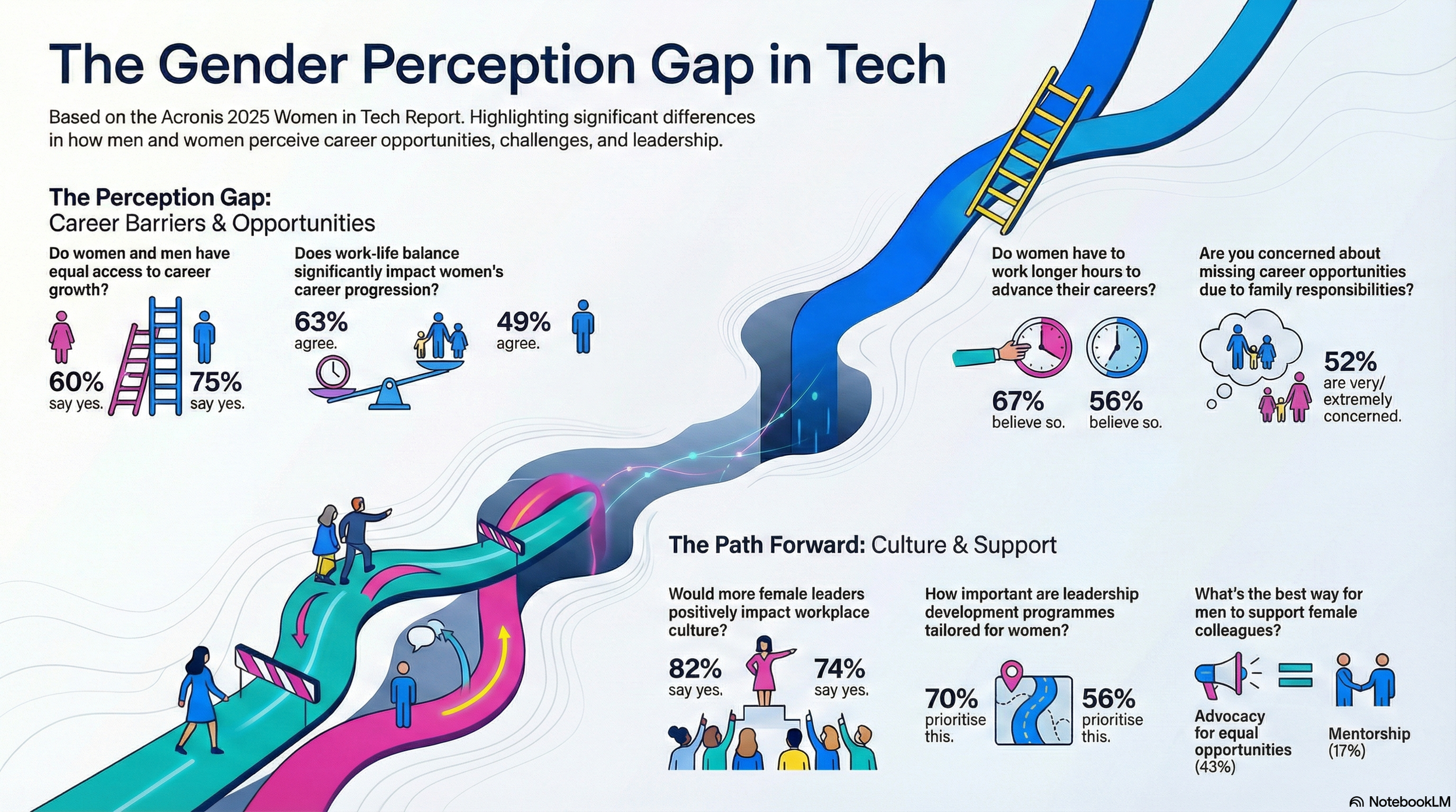

When asked whether men and women have equal access to career development opportunities in tech, 75% of men said yes. Among women, only 60% agreed. Nearly 40% of women believe access is not equal, compared with just 24% of men.

This gap matters because perception shapes decision-making. If leadership believes opportunity is broadly equal, inequality becomes reframed as a personal limitation rather than a systemic one.

The same pattern appears around bias. When asked what discourages women from entering cybersecurity careers, 41% of women cited gender bias and stereotypes as the primary barrier. Only 33% of men identified the same issue. When the question shifted to leadership roles, 41% of women again pointed to bias, compared with 36% of men.

What the report captures is not hostility, but misalignment. Bias is easier to underestimate when it does not accumulate against you.

Why This Plays Out So Sharply in India

In India, the perception gap described in the report becomes structural.

Women enter the technology workforce in relatively high numbers, particularly in engineering services, IT outsourcing, and enterprise technology. Early-career parity gives the appearance of progress. But mid-career is where trajectories diverge.

Promotion cycles begin to coincide with marriage, caregiving expectations, and unspoken assumptions about availability. The report’s finding that 52% of women are very or extremely concerned about missing career opportunities due to family responsibilities aligns closely with this reality. The fear is not emotional; it is rational in an environment where leadership visibility is often tied to physical presence and uninterrupted tenure.

Men, meanwhile, are more likely to perceive the system as broadly fair. That 75% figure on equal access is not abstract in India. It explains why advancement bottlenecks are rarely treated as organisational failures, even when patterns repeat across companies.

Work-Life Balance Is Not a Neutral Constraint

The technology industry often frames work-life balance as a universal pressure. The data shows it is anything but neutral.

According to the survey, 63% of women say work-life balance challenges significantly or extremely affect women’s career progression in tech. Only 49% of men agree. That 14-point gap is one of the largest in the report.

The divergence deepens around hours. Sixty-seven per cent of women believe they must work longer hours to advance their careers. Only 56% of men believe the same is true for women.

This is where fear of missing out becomes structural. Fifty-two per cent of women report being extremely concerned about missing career opportunities due to family responsibilities, compared with 42% of men. Only 8% of women say they are not concerned at all.

In systems where advancement is shaped by informal exposure rather than explicit criteria, absence becomes a career cost.

The Middle East: Growing Visibility

Across the Middle East, particularly in the Gulf, women’s participation in technology has grown meaningfully over the past decade. State-led digital transformation, AI strategies, and investment in STEM education have brought more women into technical roles and early leadership.

Yet the Acronis data explains why representation alone has not resolved pressure.

Only 41% of women believe work-life balance affects men and women equally. In societies where caregiving responsibilities and family expectations remain disproportionately gendered, that imbalance compounds over time. Women may be visible in technology roles, but the cost of sustained advancement remains personal rather than institutional.

Geckler sees culture as the determining factor.

“In countries where leadership and household responsibilities are more equally shared, female leadership feels normal,” she says. “In other regions, expectations around caregiving still place disproportionate pressure on women. Culture follows leadership. Always.”

Leadership Is Where the System Breaks

The survey is clearest on one point: leadership is the bottleneck.

Eighty-two percent of women believe increasing the number of women in leadership roles would have a positive impact on workplace culture. Among men, 74% agree. Women are also far more likely to describe that impact as “very positive.”

At the same time, 70% of women prioritise leadership development programs designed specifically for women, compared with 56% of men. This is not about preference. It is about recognising that the current leadership pipeline is not neutral.

“One of the most striking findings was that 82% of women said having more female leaders would improve workplace culture,” Geckler says. “Culture is shaped by how decisions are made, how conflict is handled, and how safe people feel speaking up.”

Mentorship Is Not the Same as Power

The report also punctures a comfortable assumption: that mentorship alone solves the problem.

Forty-three percent of women say men can best support them by advocating for equal opportunities. Only 17% prioritise mentorship from male colleagues. Men, by contrast, are more likely to see mentorship as the primary solution.

This distinction matters most in hierarchical cultures like India and the Middle East, where careers move through sponsorship, not advice.

“Many women underestimate themselves, even when they are objectively qualified,” Geckler says. “Mentorship creates a safe space to talk about doubts people don’t share publicly. It addresses confidence, not just competence.”

But confidence cannot compensate for systems that reward uninterrupted presence while ignoring unequal constraints.

Why the Conversation Keeps Resetting

The conversation about women in tech does not fail because the problem is unsolvable. It fails because it is framed incorrectly.

Too often, gender equity is treated as a values discussion rather than a systems problem. Progress is measured by participation rather than power, by presence rather than influence, and by intention rather than outcome.

“If diversity discussions are framed as ‘women want opportunities,’ they don’t go very far,” Geckler says. “But when they are framed around business value — better decisions, stronger teams, closer alignment with customers — then they start to matter.”

Until organisations confront the perception gap this data exposes, the industry will continue repeating the same cycle. The conversation will resurface. The language will evolve. And the underlying structures will remain largely unchanged.