Why tech jobs, startups, and companies all felt harder in 2025

For over a decade, the global tech industry lived inside a forgiving model. Growth was expected to outrun cost. Scale was supposed to justify inefficiency. Cheap capital absorbed mistakes. Global labour markets absorbed over-hiring. Regulation, when it arrived, came slowly.

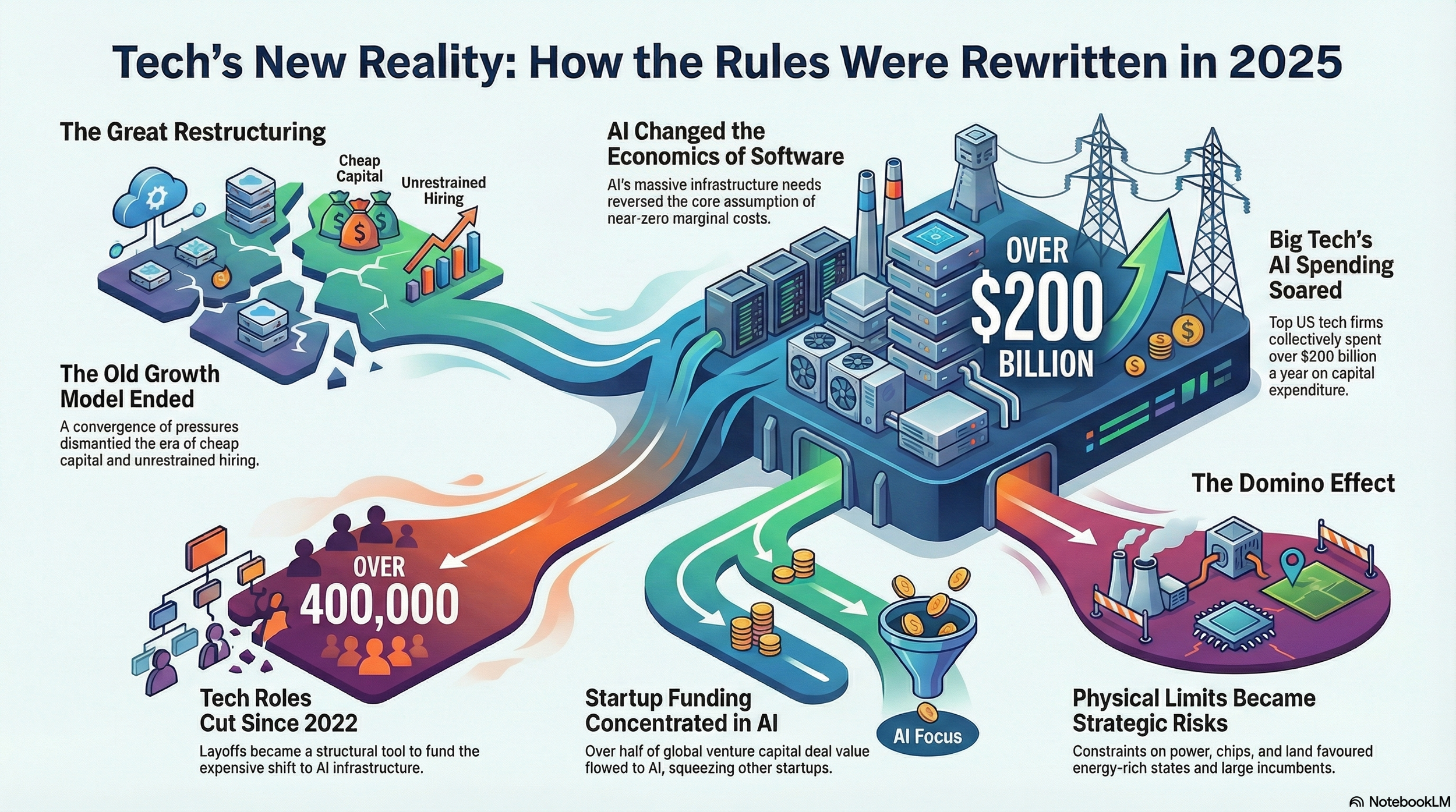

That model did not collapse in 2025. It was dismantled.

What made the year decisive was not a recession or a single regulatory shock. It was convergence. Artificial intelligence reached industrial scale at the exact moment that money became expensive, labour lost leverage, regulation hardened, and physical limits — power, chips, land — intruded into what had long been treated as a weightless digital business.

Every major tech story of 2025 fits inside that convergence. Layoffs, funding concentration, AI capital spending, geopolitics, and regulation were not separate developments. They were the same adjustment playing out across different layers of the system.

AI didn’t just change products. It changed the economics of software

On the surface, 2025 appeared to be an AI rollout year. Models improved. Enterprises moved from pilots to production. AI features spread across search, productivity tools, customer service, software development, and design.

Underneath, something more structural happened. AI has reversed one of software’s core assumptions—that marginal costs approach zero.

As reported by Reuters and the Financial Times, the largest US technology companies were collectively spending more than $200 billion annually on capital expenditures by mid-2025. A growing share of that spending was tied directly to AI infrastructure. Microsoft is guided toward an annualised capex of approximately $80 billion. Alphabet and Amazon followed similar trajectories. Meta, after declaring a “year of efficiency”, sharply increased infrastructure investment again.

These were not discretionary bets. AI raised costs before it lowered them.

Inference scaled with usage. Training required repeated computation cycles. Security and monitoring expanded as AI systems touched sensitive data. Compliance obligations multiplied as regulators moved from principles to enforcement. Energy and cooling ceased to be footnotes and became binding constraints.

This shift also explains why the Middle East entered the AI race differently in 2025. As reported by Reuters, rising AI costs triggered internal repricing and layoffs in the US. In the Gulf, the exact costs were read as an opportunity. Energy- and capital-rich states saw AI’s infrastructure demands as a reason geography mattered again.

Layoffs were not a failure. They were how companies paid for AI

The firing story belongs at the centre of 2025.

In the United States, layoffs continued. They changed form. Instead of making significant, single announcements, companies implemented rolling, targeted cuts.

As reported by Reuters, firms including Microsoft, Google, Meta, Amazon, and Intel continued to reduce headcount even as they expanded AI spending. By the end of 2025, cumulative job cuts across Big Tech since 2022 exceeded 400,000 roles globally. Tens of thousands were added during the year itself.

The cuts followed a pattern. Middle management thinned. Recruiting teams built for constant expansion shrank. Experimental product groups without clear revenue links were wound down. Trust, policy, and coordination roles — essential but difficult to price — were trimmed.

At the same time, hiring continued in AI research, infrastructure engineering, data centre operations, cybersecurity, and regulatory compliance. Labour was not being eliminated. It was being repriced to fund machines.

By late 2025, Reuters noted that markets no longer reacted to layoffs with alarm. Investors increasingly interpreted them as discipline. Workforce reduction ceased to be exceptional and became structural.

In the Middle East, the labour impact appeared differently. As reported by Reuters, AI investment surged but broad hiring did not. Employment focused on elite technical roles and state-aligned projects. Contractor churn increased. Localisation pressure intensified. Fewer people were attached to far more capital-intensive systems — without the visible shock of mass firings.

India: when scale stopped guaranteeing safety

India absorbed the same restructuring more slowly, but no less intensely.

As reported by Reuters and Indian business media, large IT services firms slowed hiring sharply in 2025. Graduate intake fell. Onboarding was delayed. Bench sizes increased. Performance exits became more common. Salary hikes flattened.

When Tata Consultancy Services reduced its workforce by roughly 2%—about 12,000 roles—the magnitude was not unprecedented. The signal was. For decades, India’s IT model rested on a simple promise: global tech demand translated into domestic employment growth.

AI weakened that promise. Clients increasingly demanded productivity gains without proportional increases in billable hours. Work that once required large teams can now be performed by smaller groups supported by automation.

India did not experience Silicon Valley-style shock firings. Job security weakened structurally rather than cyclically, which is a bigger change.

Startup funding narrowed for the same reason companies cut jobs

The funding story of 2025 often sounded contradictory. Headline totals suggested stabilisation. Founders experienced scarcity. Both were true.

According to PitchBook and WIPO, global venture capital investment in 2025 was estimated at $450–500 billion, modestly higher than in 2024. Deal counts, however, remained far below the 2021 peak. Fewer companies raised money. Those that did raised larger rounds under tighter terms.

PitchBook data showed AI accounted for more than half of global VC deal value by late 2025, despite representing a much smaller share of funded companies.

This concentration reshaped behaviour. Startups built for low-cost capital and rapid hiring proved incompatible with the new environment. Layoffs became survival tools, not reputational failures.

In India, as reported by TechCrunch and Tracxn, startups raised approximately $10–11 billion in 2022. Consumer companies with strong distribution held on. B2B and SaaS firms selling into cautious global enterprises struggled.

In the Middle East, MAGNiTT data, cited by regional outlets and referenced by Reuters, showed that funding totals were inflated by a small number of large, often state-linked rounds. Fewer deals accounted for a growing share of capital. The pattern matched the global one. Money did not disappear. It concentrated.

Power, chips, regulation, and geopolitics closed the system

By mid-2025, technology encountered constraints it could not abstract away.

As reported by Reuters, power availability has slowed data centre expansion in the US. Grid capacity, permitting delays, and local opposition became strategic risks. Energy procurement moved from operations to the boardroom. Long-term power purchase agreements, including for nuclear and large-scale renewable energy, became common.

Chips remained geopolitically constrained. Export controls stayed in place. Domestic manufacturing and sovereign compute became policy priorities.

Regulation hardened in parallel. As reported by the Financial Times, the EU AI Act moved from theory to implementation, while enforcement under the Digital Markets Act added permanent compliance costs that favoured incumbents.

This made the Middle East’s positioning legible. As Reuters reported, Gulf states offered energy security, capital, and political alignment just as constraints tightened elsewhere. AI partnerships increasingly resembled diplomatic agreements rather than pure commercial deals.

2026: what this structure makes likely

This is the system 2026 inherits.

As noted by Reuters and FT analysis, the central corporate risk is an AI return-on-investment reckoning. Boards will demand proof that AI spending reduces costs, increases revenue, or creates a durable advantage. Projects justified as “strategic” in 2025 will be reassessed. Many will be shut down even if the technology works.

For startups, the risk is distribution starvation. PitchBook analysts have warned that technical quality alone will not secure exits without scale, compliance capacity, or pricing power.

For workers, the risk is permanent volatility. Careers will feel less like ladders and more like sequences of contingent alignments.

For the Middle East, as reported by Reuters, the key risk is institutional depth. Capital and energy are abundant. Talent pipelines, governance credibility, and ecosystem maturity remain the limiting factors.

The real legacy of 2025

By the end of 2025, it became clear that the tech industry had not run out of ideas or money. What it ran out of was slack.

AI did not eliminate innovation, and it did not drain capital from the system. On the contrary, spending increased in absolute terms. However, that spending shifted into areas that behave differently from software, power, compute, chips, land, compliance, and long-lived infrastructure.

Once that shift occurred, the old growth logic ceased to function. Companies could no longer expand headcount, experimentation, and product scope simultaneously with increased capital intensity. Something had to give. In most cases, it was labour, optionality, and organisational tolerance for inefficiency.

That is what changed in 2025. Not optimism, but structure.

The industry that emerged is more constrained, more concentrated, and less forgiving. It rewards scale, distribution, and control over inputs. It punishes sprawl, redundancy, and ambiguity. For workers, it replaces the promise of upward momentum with continuous evaluation. For startups, it replaces the assumption of funding with the requirement of relevance. For governments, it turns technology from a market outcome into a capacity question.

This is why 2026 will not appear to be a rebound year. It will feel like a year in which the rules set in

And that is the environment companies and workers are now navigating — one shaped less by aspiration than by constraint.