The Startup Market in 2026: Capital, Constraints, and Survival

The startup market in 2026 will not be defined by one technology trend. It will be defined by how money moves when exits are slower, buyers are stricter, and operating costs are harder to ignore.

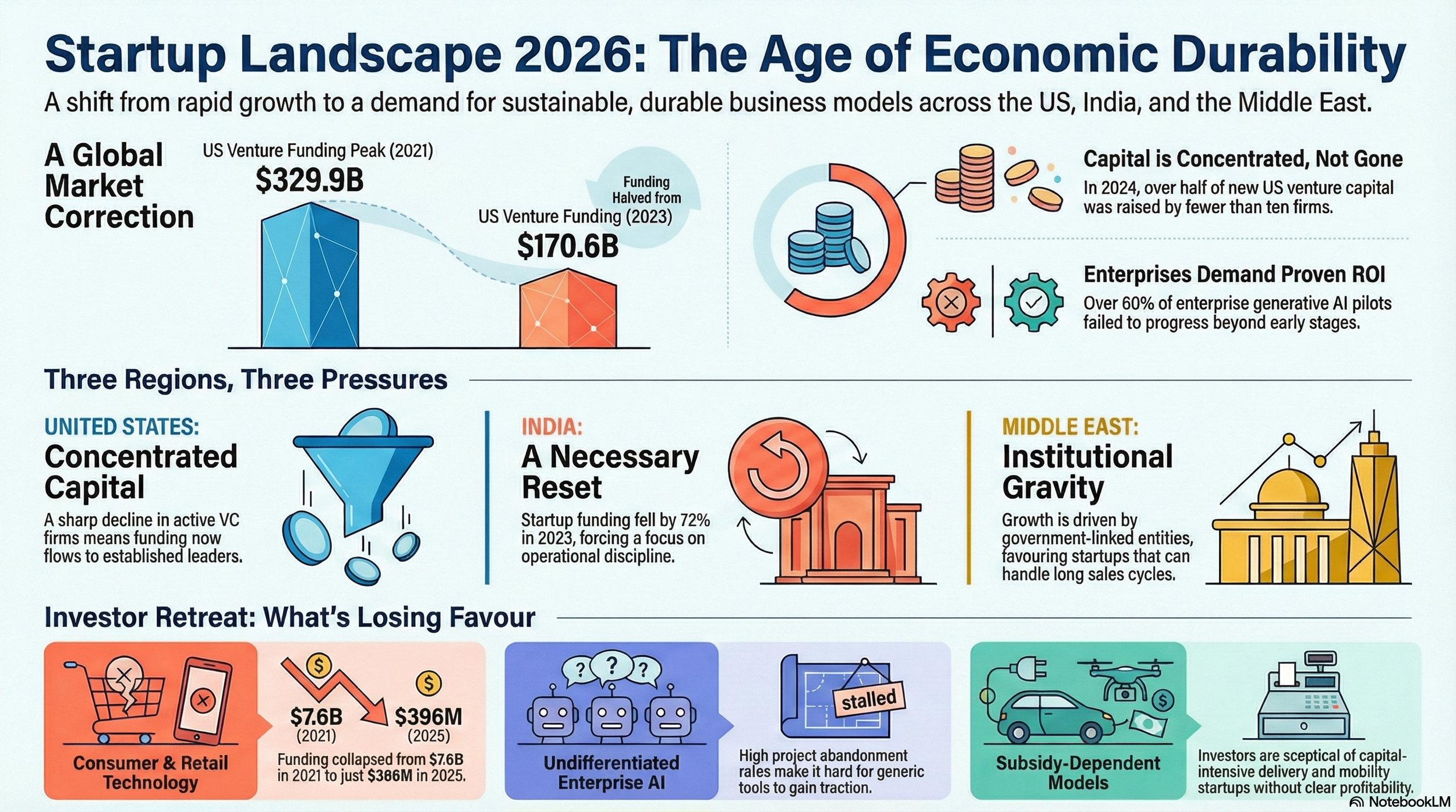

The easiest way to see this shift is to stop listening to pitches and look at three pressure points: venture funding patterns, enterprise buying behaviour, and infrastructure constraints. Across the US, India, and the Gulf, these forces are pushing startups toward the same outcome: fewer experiments and more insistence on economic durability.

The details matter because each region arrives at that outcome for different reasons.

The United States: capital is available, but it is structurally concentrated

US venture capital did not disappear after 2021. It narrowed.

PitchBook data shows US venture funding rising from $166.6B in 2020 to $329.9B in 2021, the highest level ever recorded. That surge coincided with near-zero interest rates, aggressive public market multiples, and a backlog of liquidity from stimulus-driven savings. It also coincided with a sharp rise in late-stage rounds, with median Series D+ deal sizes more than doubling between 2019 and 2021.

The reversal was equally clear. By 2023, US venture funding had fallen to $170.6B, almost exactly half of the 2021 peak. Deal count dropped to 13,608, down more than 30% from peak years. What is critical is that the recovery since then has not been broad-based. In 2024 and 2025, total funding volumes stabilised, but the number of active venture firms declined sharply.

Financial Times reporting shows the number of active US VC firms fell from 8,315 in 2021 to 6,175 in 2024, and more than half of new venture capital raised in 2024 was concentrated among fewer than ten firms.

This concentration matters because it reduces tolerance for ambiguity. Capital now flows disproportionately to companies that already look like category leaders or infrastructure anchors. PitchBook estimates that roughly one-third of global VC funding in 2024 went to AI-related companies, but within that category, a small number of firms absorbed a large share of capital through mega-rounds. For everyone else, the path to funding narrowed.

Enterprise behaviour compounds this. Between 2023 and 2025, US enterprises launched thousands of GenAI pilots. Gartner estimates that more than 60% of these initiatives failed to progress beyond early deployment, and separately predicted that 30% of GenAI projects would be abandoned after proof of concept by the end of 2025. The reasons cited were consistent across industries: unclear ROI, integration costs, weak data foundations, and unresolved security concerns.

By 2026, this failure rate translates into changed buying behaviour. Enterprises are reducing the number of vendors they test and preferring tools embedded in platforms they already trust. For startups, this shifts success away from standalone novelty and toward distribution, procurement readiness, and operational fit.

Cost pressure makes this unavoidable. For many AI-driven products, especially customer-facing systems, inference and compute costs account for 30–60% of revenue at moderate scale once cloud credits taper off. At the same time, customers are increasingly seeking fixed-price or outcome-based contracts, thereby further compressing margins. Startups that cannot demonstrate a credible path to margin improvement face resistance from both buyers and investors.

Infrastructure constraints sit underneath all of this. US data centres consumed approximately 4–6% of national electricity demand in 2024, depending on the methodology used, and multiple forecasts project that this share will rise to 8–11% by 2030, primarily driven by AI workloads. The International Energy Agency estimates global data centre electricity demand could reach approximately 945 TWh by 2030, more than double today, with AI-optimised facilities growing even faster. These pressures arise for startups due to higher cloud costs, regional capacity limits, and less predictable scaling economics.

India: the boom was real, and so was the reset

The period 2020–2022 is often described as a “boom.” The numbers are clearer than the narrative.

According to Tracxn, Indian startups raised approximately $38.5B in 2021, followed by $25B in 2022, placing India among the top three global startup markets by funding during that period. This capital inflow coincided with heightened global risk appetite, rising public-market valuations, and a strong domestic growth story. Unicorn creation accelerated, and late-stage rounds expanded rapidly.

The subsequent correction was equally sharp. In 2023, total startup funding in India fell by 72%, to roughly $7B. Funding recovered partially to $12.7B in 2024, then declined again to $10.5B in 2025, according to Tracxn’s annual reports. That pattern matters because it indicates not a temporary freeze but a lower funding baseline.

Sector data reinforces this. Indian fintech funding declined from $8.4B in 2021 to $5.4B in 2022, and then to $2B in 2023. Late-stage funding contracted more sharply than early-stage funding, signalling caution around scale and governance rather than ideation.

By 2026, this funding environment reshapes how Indian startups operate. Many Indian SaaS companies sell into US and European enterprises, where vendor consolidation and ROI scrutiny are increasing. As a result, startups that rely on low pricing without defensibility face higher churn and margin pressure. Conversely, companies that can demonstrate outcome delivery, strong retention, and operational discipline find more durable demand.

A notable response has been the rise of hybrid models. In domains such as customer operations, finance operations, compliance, and internal tooling, Indian startups increasingly bundle software with process execution. These companies often use AI extensively but do not market themselves as pure software vendors. While this caps theoretical scalability, it improves revenue stability and buyer acceptance.

The talent market reflects the same shift. Startup hiring in India slowed materially after 2022, and employee preferences shifted toward cash compensation, role clarity, and skill development rather than equity-driven upside. This forces founders to build managerial and operational structures earlier, compressing the gap between startup and traditional enterprise behaviour.

The Middle East: capital growth with institutional gravity

The Middle East startup ecosystem is often described simply as “capital-rich.” A more accurate description is that it is capitalising rapidly, but through institutions.

Between 2020 and 2024, the GCC venture ecosystem grew at an estimated 19% compound annual growth rate, reaching $1.7B in deployed venture capital in 2024, according to PwC. Deal counts also rose, indicating broader early-stage activity rather than just sovereign-led mega-deals.

That growth, however, is geographically concentrated. MAGNiTT data cited in Inc. Arabia shows that Saudi Arabia and the UAE accounted for approximately 9!% of total MENA startup funding in 2025. Saudi Arabia alone recorded $750M across 178 deals in 2024, representing 31% of MENA’s total deal count, according to the Saudi Venture Capital Company.

This concentration shapes demand. In the Gulf, large buyers are often governments, government-linked entities, or heavily regulated national champions in sectors such as energy, finance, logistics, and healthcare. Procurement processes are formal, sales cycles are long, and compliance expectations are explicit.

By 2026, this environment favours startups that can navigate institutional selling and discourages models dependent on fast, bottom-up adoption. It also introduces a structural risk: customer concentration. Startups that grow by serving one dominant buyer often struggle to generalise their product beyond that context, limiting regional or global expansion.

Data localisation further tightens constraints. Several Gulf states have strengthened requirements around data residency, cloud hosting, and national capability building. These requirements raise operating costs but also create defensibility for startups willing to invest locally. Founders who assume the region will mirror US or European deployment models often underestimate these frictions.

AI adoption will expand rapidly across government services, energy, logistics, and financial services, but social and workforce considerations matter. National employment objectives shape perceptions of automation. Startups that frame AI as a productivity enhancement and a means of capability transfer face fewer barriers than those positioned around labour replacement.

Sector-level pressure in 2026 and how it changes product strategy

These regional and macro dynamics do not hit every sector in the same way, but by 2026 the direction of travel is broadly aligned: less tolerance for loose execution, more pressure to behave like infrastructure rather than experiments.

In AI SaaS, the constraint is no more extended capability but cost, trust, and organisational fatigue. Gartner’s warning on high abandonment rates for generative AI projects reflects a deeper issue: many tools were adopted faster than enterprises could govern them. As buyers consolidate vendors and cut pilot sprawl, horizontal AI products and thin wrappers struggle to survive. Product strategy shifts toward owning specific workflows end-to-end, embedding into existing platforms, and making governance, auditability, and data control explicit. Pricing shifts from usage-based experimentation toward outcomes and efficiency, forcing teams to optimise inference costs and reliability rather than pursue model novelty.

In fintech, the pressure is structural. Funding peaked in 2021 and has not returned, and the years since have exposed the costs of scaling users faster than risk, compliance, and balance-sheet discipline can accommodate. By 2026, fintech is no longer treated as a “disruptive” category but as core financial infrastructure, expected to meet institutional standards from day one. As Michael Ayres, Group CEO of Rostro, puts it: “The future belongs to firms that combine innovation with robustness — those that invest in regulation, compliance, operational quality, and customer trust.” Product strategy reflects this reality. Startups narrow their use cases, partner with regulated institutions, and design for slower but defensible growth because, without governance, capital does not follow.

In climate and energy technology, the constraint is time as much as money. Policy support remains meaningful—particularly in the US and Gulf markets—but investor patience is waning. Technologies that require long deployment cycles or delay revenue face more stringent scrutiny. Product strategy shifts toward modular systems, retrofitting existing infrastructure, and early commercial pilots that demonstrate cash flow before scale. The emphasis moves from grand buildouts to proof that deployment risk can be contained.

In logistics and delivery, the lesson from the last decade is now reflected in prices. Public market data and private funding outcomes indicate that subsidy-led growth rarely yields durable margins. By 2026, capital favours logistics software and systems that improve asset utilisation, routing efficiency, and enterprise operations. Consumer-facing delivery platforms that rely on discounts and promotional demand struggle to raise capital unless they can demonstrate credible paths to unit-level profitability.

Across sectors, the pattern is consistent. Product strategy is being reshaped less by what technology can do, and more by what capital, regulation, and operational reality will tolerate.

What investors are quietly stepping away from

Investor behaviour already signals which categories are losing support.

Consumer and retail technology is one. PitchBook data indicate that retail startups raised $7.6B in 2021 but only $396M in 2025. This collapse reflects investor recognition that customer acquisition costs and low differentiation undermine venture-scale returns.

Undifferentiated enterprise AI tools face similar risk. With high project abandonment rates and buyer consolidation, startups without deep integration or governance struggle to convert interest into revenue.

Capital-intensive models that depend on subsidies, particularly for delivery and mobility, face sustained scepticism. Growth without pricing power has repeatedly failed to produce durable businesses.

Fintech, lacking regulatory depth, also faces declining tolerance. The sharp decline in funding from 2021 to 2023 illustrates how quickly investor sentiment can turn when governance lags behind scale.

Finally, investors are retreating from the “middle” of the venture market. The decline in active VC firms and the concentration of capital among a few large players reduce funding options for companies that are good but not dominant. This is not ideological. It is structural.