Adobe Finds AI Everywhere in the Middle East, but Real Returns Are Still Elusive

For years, digital transformation in the Middle East was framed as a future destination. It appeared in national visions, conference panels, and executive speeches, often tied to diversification away from oil and toward knowledge-based economies. What the latest research from Adobe makes clear is that this phase is largely over. The region is no longer debating whether to invest in digital capabilities. It is now grappling with a more uncomfortable question: why so much investment has yet to translate into consistent, measurable impact?

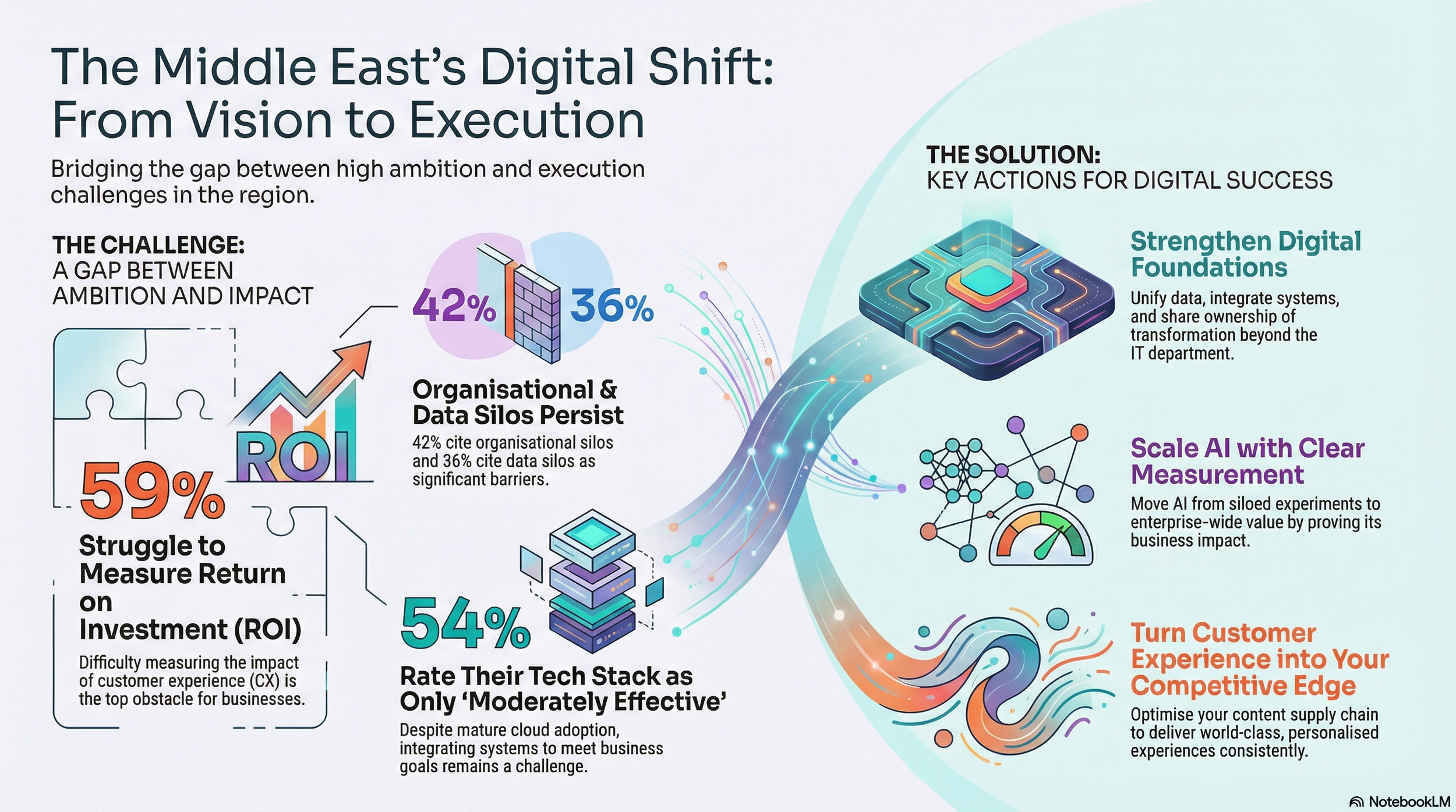

Based on a survey of 200 large enterprises across Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Qatar, and Kuwait, the report paints a picture of momentum paired with friction. Cloud infrastructure is broadly in place, AI experimentation is widespread, and customer experience has become a board-level priority. Yet execution gaps, organisational silos, and weak measurement continue to dilute returns.

As Wael Fakharany, Director of Middle East and Africa at Adobe, put it, “Across the Middle East, digital ambition is high, and investment in AI, data, and customer experience is picking up at a serious pace. What now determines success is not intent, but execution, and how well organisations connect systems, teams, and data.”

Digital transformation as national strategy

Unlike in the US, where competition between companies often drives digital change, or in Europe, where regulation plays a defining role, the Middle East’s digital push has been led from the top. Governments across the Gulf have positioned digital transformation as an economic necessity, using capital spending, policy reform, and public-sector digitisation to accelerate change.

The logic is straightforward. Automation and digital productivity are seen as essential to creating jobs, attracting foreign investment, and sustaining growth in a post-oil world. Unsurprisingly, nearly half of surveyed businesses cite economic diversification and productivity gains as the most important forces shaping their digital strategies.

This top-down momentum is reinforced by bottom-up pressure from consumers. The region’s demographics are young by global standards, and social media penetration in countries such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia is close to universal. In practice, this means digital interaction is not an alternative channel but the default one.

Affluence raises expectations, not patience

Wealth further sharpens these expectations. In high-income markets such as Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, consumers expect speed, relevance, and personalisation as a basic service standard. Digital excellence is not viewed as innovation; it is seen as competence.

The report highlights that this dynamic turns digital investment into a revenue lever rather than a defensive cost. Affluent, mobile consumers are more willing to pay for premium, digital-first services, but they are also quicker to abandon brands that feel slow or fragmented. Even in Egypt, where GDP per capita is far lower, rapid digital adoption among a young population signals where future demand is headed.

Confident on CX, uncertain on returns

Customer experience sits at the centre of this shift. Eighty-five percent of organisations surveyed rate their ability to deliver personalised, unified customer experiences as “good” or “excellent.” On the surface, this suggests a region that believes it is doing the right things.

However, nearly 60% of respondents also admit they struggle to measure the return on investment of those same experiences. This contradiction runs throughout the research. Companies know CX matters, but many cannot clearly link digital initiatives to revenue growth, customer lifetime value, or retention.

Organisational silos are a major part of the problem. Data remains fragmented across marketing, operations, and IT systems, making it difficult to build a single view of the customer or act on insights in real time. As the report notes, without integrated data and shared KPIs, personalisation becomes episodic rather than systemic.

Who really owns digital change?

Another structural tension lies in ownership. In 62% of organisations, responsibility for executing digital initiatives sits with the CIO or CTO. This has helped establish cloud platforms and core infrastructure, but it has also limited broader impact.

Marketing, operations, and frontline teams often remain downstream consumers of technology rather than co-owners of transformation. Cross-functional digital teams, now common in North America and Europe, are still rare in the Middle East. Roles such as Chief Digital Officer or Chief Experience Officer exist more as concepts than as clearly empowered positions.

The result is that digital transformation is still treated, in many organisations, as a technology programme rather than an organisational redesign.

AI everywhere, impact still uneven

Nowhere is this clearer than in artificial intelligence. Nearly nine in ten organisations are experimenting with or deploying AI, and more than half are running pilot projects. AI is already being used for analytics, automation, chatbots, and content creation.

Yet only 15% of respondents believe AI is currently the most influential technology for profitability and growth. The gap reflects a familiar pattern. AI is often layered onto existing processes rather than embedded into how decisions are made, how content is produced, or how customer journeys are orchestrated end-to-end.

As Fakharany noted, “There is a real opportunity to move AI out of isolated use cases and into everyday execution. That requires shared learning across teams and platforms that integrate AI directly into business workflows.”

The hidden bottleneck: content and execution

One of the most revealing sections of the research focuses on the content supply chain. As personalisation increases, so does the demand for content across channels, formats, and languages. Yet only 28% of organisations rate their content operations as very efficient.

Maintaining brand consistency across markets is the single biggest challenge, followed closely by the difficulty of scaling content and measuring its ROI. Half of organisations now use AI extensively in content creation, but many still struggle with fragmented workflows and limited visibility across agencies and teams.

This is where execution becomes visible to customers. Slow updates, inconsistent messaging, and generic experiences are not abstract organisational problems; they are felt directly in the market.

From vision to credibility

Taken together, the findings suggest the Middle East is entering a more demanding phase of its digital journey. The era of announcing transformation is over. Infrastructure is largely in place. Experimentation is widespread. What remains unresolved is integration, ownership, and measurement.

The next phase will reward organisations that treat digital transformation not as a series of tools, but as a coordinated system linking data, AI, content, and customer journeys. Those that succeed will not just meet rising expectations at home, but help define how emerging markets globally turn digital ambition into a durable economic advantage.

The question is no longer whether the Middle East can build digital capability. The evidence suggests it already has. The question now is whether it can turn that capability into consistent, provable results.